http://longislandreport.org/multimedia/cancercare-raises-over-100000-for-lung-cancer-services/25191

Five Years Later: Superstorm Sandy’s Affect on Lindenhurst

By Chris Birsner and Jessica Jahn

The End Of Hofstra Football

It has been almost eight years since Hofstra football played its last game on November 21st, 2009. The final score was 52-38 Hofstra over UMass. The Pride had won its final game of the season in front of their home crowd at James M. Shuart Stadium.

The football program was participating in offseason winter workouts when a text alert was sent to all players the morning of December 3rd. “Urgent: team meeting @ 10 in the Pride Lounge,” the text read.

“When we got there, all the chairs were lined up in front of a podium. It was very strange,” said Keith Ferrara, former Hofstra defensive back, “There were off duty public safety officers there and when we asked them what was going on, they shut us down. They treated us very coldly.

“I’ll tell you this; the last thing on anyone’s mind was that they were going to shut down the football program.”

When all the players arrived, then-athletics director Jack Hayes stood at the podium and delivered the unthinkable news to them: their football program was no more. This came after a vote the night before by Hofstra University’s Board of Trustees where they weighed the costs of keeping the program alive and ultimately decided to eliminate it after a 72-year run. No other sports program was touched.

“My life was ripped right from underneath me. I gave everything I had to that program,” said Tom Ottaiano, former Hofstra offensive lineman.

The 84 players on the Hofstra football roster were given the option to stay at the school and keep their scholarship, or transfer to continue playing football at a different institution. Head Coach Dave Cohen would get to keep his contract until it expired or until he found a new job. The rest of coaching staff stayed on the payroll until August 31st and were given assistance in finding new jobs. According to the New York Times, all assistants were flown to a coaching convention where they could look for new employers.

There were other options on the table for the board. Hofstra was a member of the Football Championship Subdivision (FCS), otherwise known as Division I-AA. Right above FCS is the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS), known as Division I-A. This is where programs such as Alabama, Florida State, and Oklahoma reside. A move to the highest subdivision in college football may have brought more coverage and revenue to Hofstra, but university president Stuart Rabinowitz felt it was a waste of time.

“The Southeastern Conference and the Big Ten weren’t calling us,” Rabinowitz told the New York Times, “It proved to be impossible to justify the money and upgrades that would be necessary for that jump.”

The end of the football program was a surprise to many, but it had been on the decline for years. Home games averaged 4,260 fans per game, which barely filled the 12,000-seat stadium. 500 students on average attended football games while 900 attended basketball games. In the same comparison, the football program sold 172 season tickets while the basketball program sold 750.

According to Hofstra’s website, the football program costed $4.5 million a year, which included scholarships. Athletics as a whole costs the school $18 million, excluding football.

“In the long run,” Rabinowitz said via the 2009 press release, “we can touch and improve the lives of more students by investing in new and enhanced academic initiatives and increasing funds for need-based scholarships.”

Rabinowitz was not in the room when the news was announced to the players, which Ferrara felt that he should have along with the rest of the board of trustees.

“He should be the one that delivers the news to the players,” said Ferrara, “I felt like they were treating us as numbers instead of people. If [the board of trustees] really learned the value of this program and how it affected the people in it, they would never make this decision.”

The press release by Hofstra after the football program shut down said that they would “reallocate” the money used on the program to other parts of academia, such as sciences, engineering, and public health. It has not been confirmed what specifically the money was used for and how it has improved the university. Hofstra did start a medical school in 2011 and many believe the football program’s money was used to pay for it. This has not been confirmed. Multiple phone calls and e-mails to Hofstra officials were not returned.

Despite losing their program, most of the football players were able to transition to the next phase of their lives, whether that was playing football somewhere else or continuing their studies at Hofstra.

Offensive lineman Ottaiano made the decision to transfer from Hofstra to the University of Monmouth. “It was the best decision I’ve ever made,” said Ottaiano.

He went on to play at the school for the 2010 season and he was signed as an undrafted free agent by the New York Jets in 2011. He never made the final roster. Ottaiano is now a CEO and founder of digital marketing company Today’s Business. He started the company with former Hofstra teammate Chaz Cervino.

Defensive back Ferrara was extended an offer to play at Wagner College in Staten Island. However, he never got to play as he suffered a severe lower leg injury that ended his playing career.

“It went undiagnosed for a few days and once I finally got to the hospital, [the doctors] thought they had to amputate my leg at that point,” said Ferrara. “You can imagine how that feels to be told on December 3rd that you can’t play football [at Hofstra] anymore and then on December 19th to be told that you weren’t going to walk again. Everything that could’ve gone wrong that month went wrong.”

Ferrara was able to fight through it. After many surgeries and physical therapy, he was able to get his foot moving again.

“I was never going to let that time period define me. I am as good as I can be today,” said Ferrara, “You would never know that there was anything wrong with me.”

Despite not being able to play football, Ferrara remained at Hofstra as a graduate assistant to strength and condition coaches and now works as Head strength and conditioning coach at Adelphi University.

Hofstra football’s impact stretched beyond Long Island. There have been many players associated with the program that have made their way to the NFL. Wide receiver Wayne Chrebet, who played on the team when they were the “Flying Dutchmen,” broke school records for touchdowns in a game (5), season (16), and career (31). He signed as an undrafted free agent with the New York Jets and played 11 seasons with the team. He was inducted into the Jets Ring of Honor in 2014.

When the program shut down, Chrebet was heartbroken by the news.

“I was shocked,” Chrebet told the New York Daily News, “It’s a shame. I’m thinking about the kids that are there. They left home and picked Hofstra to go play football. Now they’re stuck with a school without a team.”

Other important figures to come out of Hofstra football include Marques Colston, who went from a prolific career at Hofstra to a Hall-of-Fame caliber career for the New Orleans Saints. After being drafted in the seventh round in 2006, Colston set franchise records in career receiving yards and receiving touchdowns. He helped lead the team to Super Bowl XLIV, where they defeated the Indianapolis Colts in 2010. Dan Quinn, current head coach of the reigning NFC Champion Atlanta Falcons, spent five years (1996-2000) as a defensive coach at Hofstra before getting his first NFL job with the San Francisco 49ers.

Over its 72-year history, Hofstra football had a final record of 403 wins, 268 losses, and 11 ties and finished with 45 winning seasons and three seasons at .500. The team had five playoff berths, one conference title (Atlantic-10), and two playoff wins, but never won a championship.

The program may be dead, but the memories that Hofstra football brought Long Island and the players the program introduced to the world will never be forgotten.

Are NFL Teams Getting Their Money’s Worth?

Twelve games into the 2016 season, NFL teams are either feeling pretty good about the investments they made heading into 2016 or disappointed that the players they paid aren’t getting the job done.

The general manager of each team spends most of the offseason trying to figure out if a player deserves the amount of money they are asking for, whether a player deserves an extension or if a player doesn’t deserve to even remain on the team. But the ultimate test to see if they did a good job in making those decisions is three quarters of the way through the season.

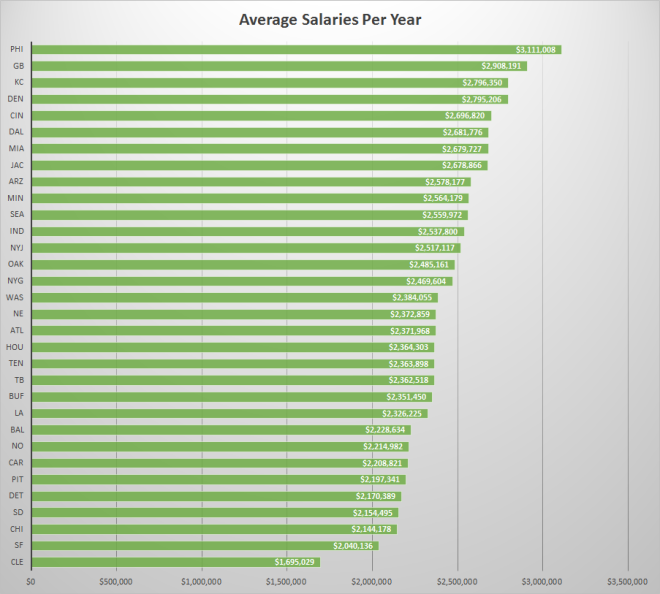

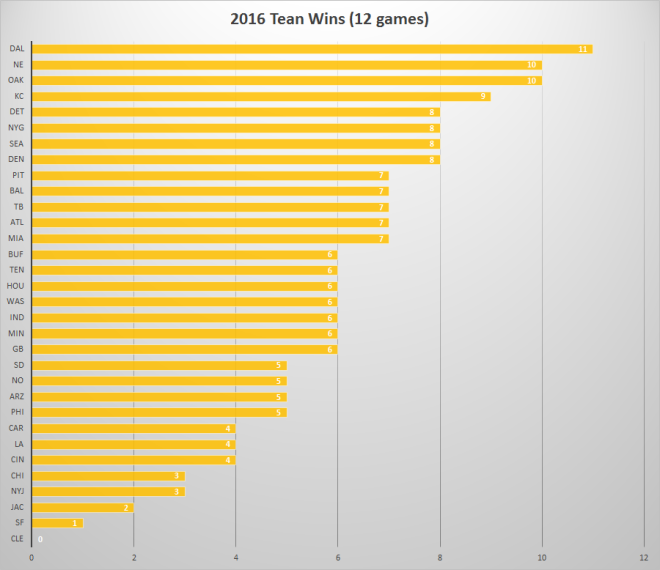

For example, the Dallas Cowboys spend an average $2.7 million per player on their roster. That is the sixth highest average in the league. So far, it has paid off for the team as they are currently the best team in the league with an 11-1 record through 12 games. They are the only team thus far that are a lock for the playoffs. The Cleveland Browns, meanwhile, are spending an average of only $1.7 million, the lowest average in the league. They are currently the NFL’s worst team with zero wins this season and twelve straight losses.

However, that kind of trend doesn’t always go like that. The Philadelphia Eagles, for example, spend an average of $3.1 million per player, the most in the NFL. However, the Eagles have only 5 wins this season and are at the bottom of their division. Meanwhile, the Detroit Lions spend an average of $2.2 million, the fifth least in the league, and are currently on top of their division and a few wins away from getting a playoff berth. The Lions are getting a bargain on a great team while the Eagles are spending a fortune on a mediocre team.

Below is data from Spotrac that lists all 32 teams from the highest average amount spent on a player to the lowest average amount. Below that chart is the current win totals for all 32 teams from the NFL’s website, listed from most wins to least.

(Data via Spotrac as of December 6th, 2016)

Storify on Colin Kaepernick

My Storify piece on Colin Kaepernick-

https://storify.com/chrisbirsner/colin-kapernick-begins-a-movement